US President Donald Trump has hit China with a second tariff in as many months, which means imports from there now face a levy of at least 20%. This is his latest salvo against Beijing, which already faces steep US tariffs, from 100% on Chinese-made electric vehicles to 15% on clothes and shoes.

Trump's tariffs strike at the heart of China's manufacturing juggernaut - a web of factories, assembly lines and supply chains that manufacture and ship just about everything, from fast fashion and toys to solar panels and electric cars. China's trade surplus with the world rose to a record $1tn (£788bn) in 2024, on the back of strong exports ($3.5tn), which surpassed its import bill ($2.5tn).

It has long been the world's factory - it has thrived because of cheap labour and state investment in infrastructure ever since it opened its economy to global business in the late 1970s. So how badly could Trump's trade war hurt China's manufacturing success?

Tariffs are taxes charged on goods imported from other countries. Most tariffs are set as a percentage of the value of the goods, and it's generally the importer who pays them. So, a 10% tariff means a product imported to the US from China worth $4 would face an additional $0.40 charge applied to it.

Increasing the price of imported goods is meant to encourage consumers to buy cheaper domestic products instead, thus helping to boost their own economy's growth. Trump sees them as a way of growing the US economy, protecting jobs and raising tax revenue. But economic studies of the impact of tariffs which Trump imposed during his first term in office, suggest the measures ultimately raised prices for US consumers.

Trump has said his most recent tariffs are aimed at pressuring China to do more to stop the flow of the opioid fentanyl to the US. He also imposed 25% tariffs on America's neighbours Mexico and Canada, saying its leaders were not doing enough to crack down on the cross-border illegal drug trade.

Exports have been the "saving grace" of China's economy and if the taxes linger, exports to the US could drop by a quarter to a third, Harry Murphy Cruise, an economist at Moody's analytics, told the BBC. The sheer value of China's exports - which account for a fifth of the country's earnings - means that a 20% tariff could weaken demand from overseas and shrink the trade surplus.

"The tariffs will hurt China," Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis in Hong Kong, told the BBC. "They really need to do much more. They need to do what Xi Jinping has already said - boost domestic demand." That is a tall task in an economy where the property market is slumping and disillusioned youth are struggling to find high-paying jobs.

Chinese people have not been spending enough to recharge the economy - and Beijing has just announced a slew of stimulus measures to boost consumption. While tariffs can slow Chinese manufacturing, they cannot stop or replace it that easily, analysts say.

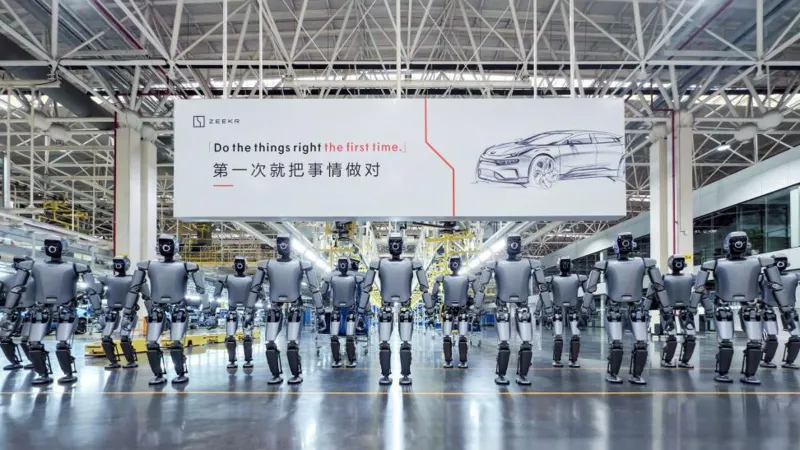

"Not only is China the big exporter, it is sometimes the only exporter like for solar panels. If you want solar panels you can only go to China," Ms Garcia-Herrero said. China had begun pivoting from making garments and shoes to advanced tech such as robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) long before Trump became president. And that has given China an "early mover" advantage, not to mention the scale of production in the world's second-largest economy.

Chinese factories can produce high-end tech in large quantities at a low cost, said Shuang Ding, chief China economist at Standard Chartered. "It's really difficult to find a replacement... China's status as a market leader is very difficult to topple."

TRENDING NOW

›-

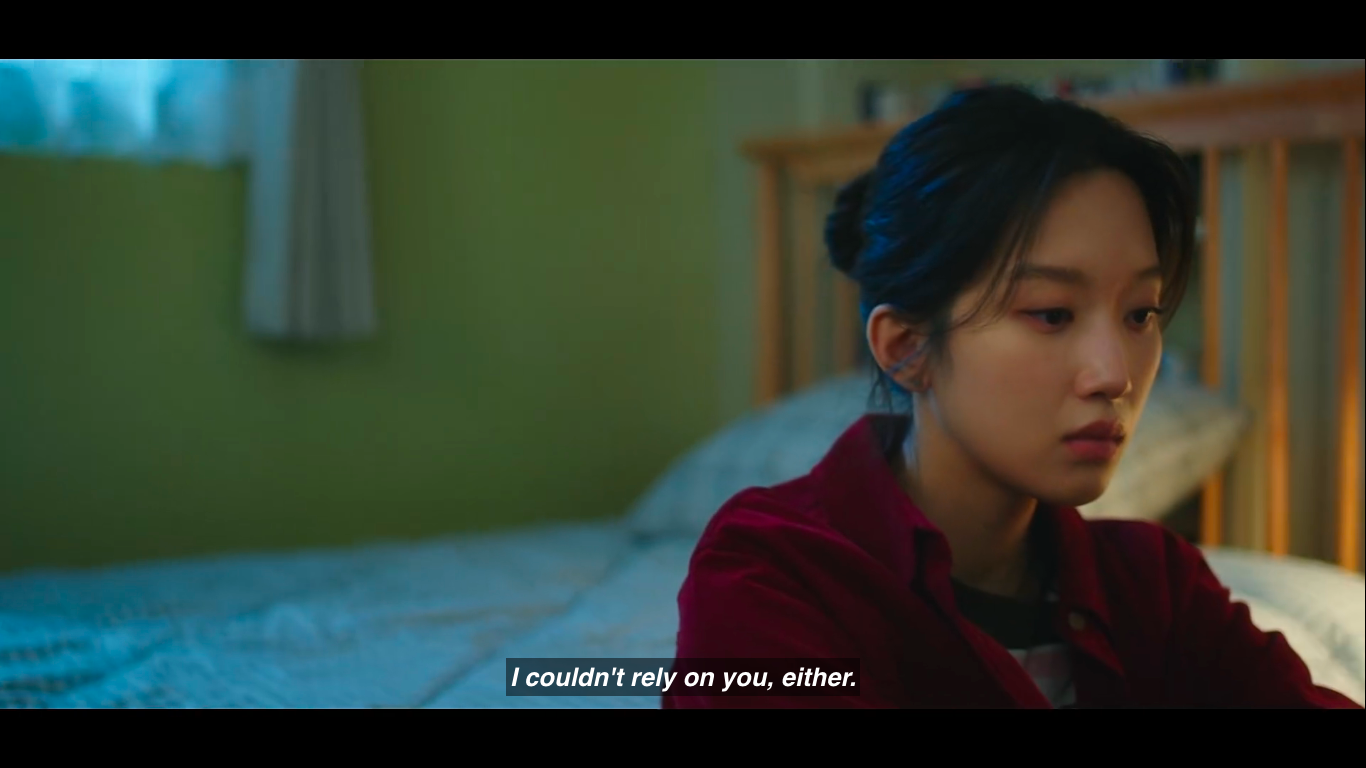

2 Difficult And 2 Happy Moments For Mun Ka Young & Choi Hyun Wook In Episodes 9-10 Of "My Dearest Nemesis"

2 Difficult And 2 Happy Moments For Mun Ka Young & Choi Hyun Wook In Episodes 9-10 Of "My Dearest Nemesis"

-

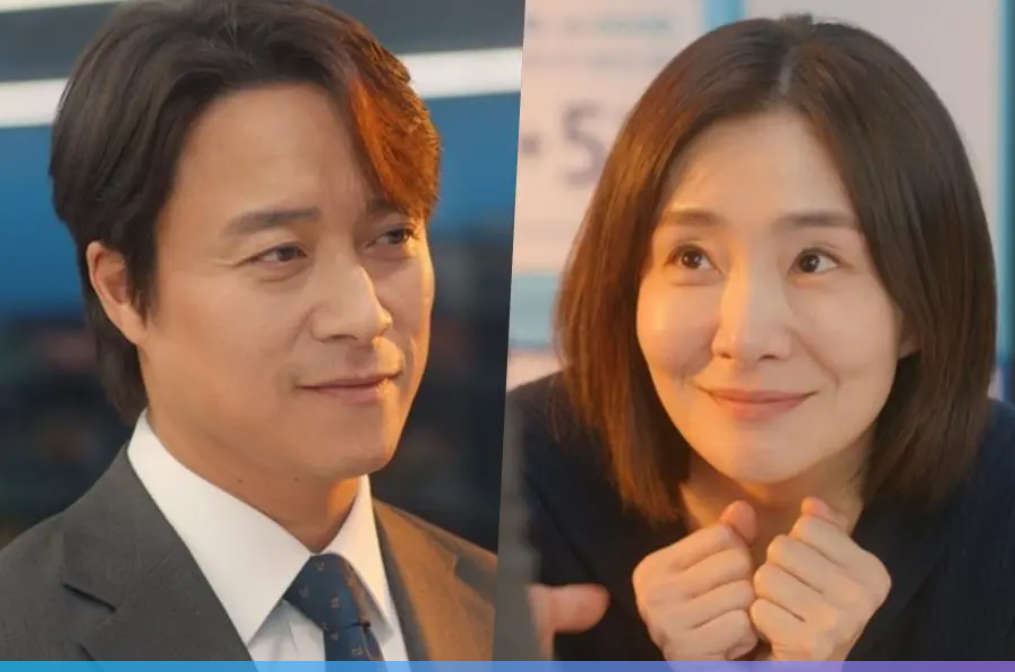

Jeong Eun Ji, Jung Wook Jin, And More Are Co-Workers In Upcoming Drama "Pump Up The Healthy Love"

Jeong Eun Ji, Jung Wook Jin, And More Are Co-Workers In Upcoming Drama "Pump Up The Healthy Love"

-

Enough war’: Why Gazans are protesting Hamas now

Enough war’: Why Gazans are protesting Hamas now

-

Elton John thinks recent musical flopped because 'it was too political for America': 'They don't really get irony'

Elton John thinks recent musical flopped because 'it was too political for America': 'They don't really get irony'

-

Choi Dae Chul And Park Hyo Joo Grow Fonder Of Each Other In "For Eagle Brothers"

Choi Dae Chul And Park Hyo Joo Grow Fonder Of Each Other In "For Eagle Brothers"

-

ENHYPEN To Appear On "Jimmy Kimmel Live!" Ahead Of Coachella Performance

ENHYPEN To Appear On "Jimmy Kimmel Live!" Ahead Of Coachella Performance

-

'I was brought back from the brink of death': Taiwanese singer Tank successfully receives heart and liver transplant

'I was brought back from the brink of death': Taiwanese singer Tank successfully receives heart and liver transplant

-

Thousands of Jewish worshippers visit Jerusalem holy site as Israeli lawmaker boasts ‘Arabs aren’t allowed to come near us’

Thousands of Jewish worshippers visit Jerusalem holy site as Israeli lawmaker boasts ‘Arabs aren’t allowed to come near us’

.webp)